of a single penny. As for Gibbon and

the bulbous historians, though a whole perusal would outlast the

summer and stretch to the colder months, yet with patience they could

be got through. However, before the end was even a hasty reader whose

eye was nimble on the would be blowing on his nails and pulling his

tails between him and the November wind.

But the habit of reading at the open stalls was not only with the poor.

You will remember that Mr. Brownlow was addicted. Really, had not

the Artful Dodger stolen his pocket handkerchief as he was thus

engaged upon his book, the whole history of Oliver Twist must have

been quite different. And Pepys himself, Samuel Pepys, F.R.S., was

guilty. "To Paul's Church Yard," he writes, "and there looked upon the

second part of Hudibras, which I buy not, but borrow to read." Such

parsimony is the curse of authors. To thumb a volume cheaply around a

neighborhood is what keeps them in their garrets. It is a less offence to

steal peanuts from a stand. Also, it is recorded in the life of Beau Nash

that the persons of fashion of his time, to pass a tedious morning "did

divert themselves with reading in the booksellers' shops." We may

conceive Mr. Fanciful Fopling in the sleepy blink of those early hours

before the pleasures of the day have made a start, inquiring between his

yawns what latest novels have come down from London, or whether a

new part of "Pamela" is offered yet. If the post be in, he will prop

himself against the shelf and--unless he glaze and nod--he will read

cheaply for an hour. Or my Lady Betty, having taken the waters in the

pump-room and lent her ear to such gossip as is abroad so early, is now

handed to her chair and goes round by Gregory's to read a bit. She is

flounced to the width of the passage. Indeed, until the fashion shall

abate, those more solid authors that are set up in the rear of the shop,

must remain during her visits in general neglect. Though she hold

herself against the shelf and tilt her hoops, it would not be possible to

pass. She is absorbed in a book of the softer sort, and she flips its pages

against her lap-dog's nose.

But now behold the student coming up the street! He is clad in shining

black. He is thin of shank as becomes a scholar. He sags with

knowledge. He hungers after wisdom. He comes opposite the bookshop.

It is but coquetry that his eyes seek the window of the tobacconist. His

heart, you may be sure, looks through the buttons at his back. At last he

turns. He pauses on the curb. Now desire has clutched him. He jiggles

his trousered shillings. He treads the gutter. He squints upon the rack.

He lights upon a treasure. He plucks it forth. He is unresolved whether

to buy it or to spend the extra shilling on his dinner. Now all you cooks

together, to save your business, rattle your pans to rouse him! If within

these ancient buildings there are onions ready peeled--quick!--throw

them in the skillet that the whiff may come beneath his nose! Chance

trembles and casts its vote--eenie meenie--down goes the shilling--he

has bought the book. Tonight he will spread it beneath his candle. Feet

may beat a snare of pleasure on the pavement, glad cries may pipe

across the darkness, a fiddle may scratch its invitation--all the rumbling

notes of midnight traffic will tap in vain their summons upon his

window.

Any Stick Will Do To Beat A Dog

Reader, possibly on one of your country walks you have come upon a

man with his back against a hedge, tormented by a fiend in the likeness

of a dog. You yourself, of course, are not a coward. You possess that

cornerstone of virtue, a love for animals. If at your heels a dog sniffs

and growls, you humor his mistake, you flick him off and proceed with

unbroken serenity. It is scarcely an interlude to your speculation on the

market. Or if you work upon a sonnet and are in the vein, your thoughts,

despite the beast, run unbroken to a rhyme. But pity this other whose

heart is less stoutly wrapped! He has gone forth on a holiday to take the

country air, to thrust himself into the freer wind, to poke with his stick

for such signs of Spring as may be hiding in the winter's leaves. Having

been grinding in an office he flings himself on the great round world.

He has come out to smell the earth. Or maybe he seeks a hilltop for a

view of the fields that lie

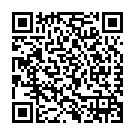

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.