The Problems of Philosophy

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Problems of Philosophy, by Bertrand Russell (#4 in

our series by Bertrand Russell)

Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for

your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg

eBook.

This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file.

Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission.

Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project

Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your

specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about

how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved.

**Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts**

**eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971**

*****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!*****

Title: The Problems of Philosophy

Author: Bertrand Russell

Release Date: June, 2004 [EBook #5827] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of

schedule] [This file was first posted on September 10, 2002]

Edition: 10

Language: English

Character set encoding: ASCII

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK, THE PROBLEMS OF

PHILOSOPHY ***

This eBook was prepared by Gordon Keener .

The Problems of Philosophy Bertrand Russell

PREFACE

In the following pages I have confined myself in the main to those problems of

philosophy in regard to which I thought it possible to say something positive and

constructive, since merely negative criticism seemed out of place. For this reason, theory

of knowledge occupies a larger space than metaphysics in the present volume, and some

topics much discussed by philosophers are treated very briefly, if at all.

I have derived valuable assistance from unpublished writings of G. E. Moore and J. M.

Keynes: from the former, as regards the relations of sense-data to physical objects, and

from the latter as regards probability and induction. I have also profited greatly by the

criticisms and suggestions of Professor Gilbert Murray.

1912

CHAPTER I

APPEARANCE AND REALITY

Is there any knowledge in the world which is so certain that no reasonable man could

doubt it? This question, which at first sight might not seem difficult, is really one of the

most difficult that can be asked. When we have realized the obstacles in the way of a

straightforward and confident answer, we shall be well launched on the study of

philosophy--for philosophy is merely the attempt to answer such ultimate questions, not

carelessly and dogmatically, as we do in ordinary life and even in the sciences, but

critically, after exploring all that makes such questions puzzling, and after realizing all

the vagueness and confusion that underlie our ordinary ideas.

In daily life, we assume as certain many things which, on a closer scrutiny, are found to

be so full of apparent contradictions that only a great amount of thought enables us to

know what it is that we really may believe. In the search for certainty, it is natural to

begin with our present experiences, and in some sense, no doubt, knowledge is to be

derived from them. But any statement as to what it is that our immediate experiences

make us know is very likely to be wrong. It seems to me that I am now sitting in a chair,

at a table of a certain shape, on which I see sheets of paper with writing or print. By

turning my head I see out of the window buildings and clouds and the sun. I believe that

the sun is about ninety-three million miles from the earth; that it is a hot globe many

times bigger than the earth; that, owing to the earth's rotation, it rises every morning, and

will continue to do so for an indefinite time in the future. I believe that, if any other

normal person comes into my room, he will see the same chairs and tables and books and

papers as I see, and that the table which I see is the same as the table which I feel

pressing against my arm. All this seems to be so evident as to be hardly worth stating,

except in answer to a man who doubts whether I know anything. Yet all this may be

reasonably doubted, and all of it requires much careful discussion before we can be sure

that we have stated it in a form that is wholly true.

To make our difficulties plain, let us concentrate attention on the table. To the eye it is

oblong, brown and shiny, to the touch it is smooth and cool and hard; when I tap it, it

gives

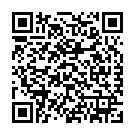

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.