poor last of the family, was without

the pale, simply because I, too, was a novelist. I explained these things

to Callan and he commented on them, found it strange how small or

how large, I forget which, the world was. Since his own apotheosis

shoals of Callans had claimed relationship.

I ate my breakfast. Afterward, we set about the hatching of that

article--the thought of it sickens me even now. You will find it in the

volume along with the others; you may see how I lugged in Callan's

surroundings, his writing-room, his dining-room, the romantic arbour

in which he found it easy to write love-scenes, the clipped trees like

peacocks and the trees clipped like bears, and all the rest of the

background for appropriate attitudes. He was satisfied with any

arrangements of words that suggested a gentle awe on the part of the

writer.

"Yes, yes," he said once or twice, "that's just the touch, just the

touch--very nice. But don't you think...." We lunched after some time.

I was so happy. Quite pathetically happy. It had come so easy to me. I

had doubted my ability to do the sort of thing; but it had written itself,

as money spends itself, and I was going to earn money like that. The

whole of my past seemed a mistake--a childishness. I had kept out of

this sort of thing because I had thought it below me; I had kept out of it

and had starved my body and warped my mind. Perhaps I had even

damaged my work by this isolation. To understand life one must

live--and I had only brooded. But, by Jove, I would try to live now.

Callan had retired for his accustomed siesta and I was smoking pipe

after pipe over a confoundedly bad French novel that I had found in the

book-shelves. I must have been dozing. A voice from behind my back

announced:

"Miss Etchingham Granger!" and added--"Mr. Callan will be down

directly." I laid down my pipe, wondered whether I ought to have been

smoking when Cal expected visitors, and rose to my feet.

"You!" I said, sharply. She answered, "You see." She was smiling. She

had been so much in my thoughts that I was hardly surprised--the thing

had even an air of pleasant inevitability about it.

"You must be a cousin of mine," I said, "the name--"

"Oh, call it sister," she answered.

I was feeling inclined for farce, if blessed chance would throw it in my

way. You see, I was going to live at last, and life for me meant

irresponsibility.

"Ah!" I said, ironically, "you are going to be a sister to me, as they

say." She might have come the bogy over me last night in the

moonlight, but now ... There was a spice of danger about it, too, just a

touch lurking somewhere. Besides, she was good-looking and well set

up, and I couldn't see what could touch me. Even if it did, even if I got

into a mess, I had no relatives, not even a friend, to be worried about

me. I stood quite alone, and I half relished the idea of getting into a

mess--it would be part of life, too. I was going to have a little money,

and she excited my curiosity. I was tingling to know what she was

really at.

"And one might ask," I said, "what you are doing in this--in this...." I

was at a loss for a word to describe the room--the smugness parading as

professional Bohemianism.

"Oh, I am about my own business," she said, "I told you last

night--have you forgotten?"

"Last night you were to inherit the earth," I reminded her, "and one

doesn't start in a place like this. Now I should have gone--well--I

should have gone to some politician's house--a cabinet minister's--say

to Gurnard's. He's the coming man, isn't he?"

"Why, yes," she answered, "he's the coming man."

You will remember that, in those days, Gurnard was only the dark

horse of the ministry. I knew little enough of these things, despised

politics generally; they simply didn't interest me. Gurnard I disliked

platonically; perhaps because his face was a little enigmatic--a little

repulsive. The country, then, was in the position of having no

Opposition and a Cabinet with two distinct strains in it--the Churchill

and the Gurnard--and Gurnard was the dark horse.

"Oh, you should join your flats," I said, pleasantly. "If he's the coming

man, where do you come in?... Unless he, too, is a Dimensionist."

"Oh, both--both," she answered. I admired the tranquillity with which

she converted my points into her own. And I was very happy--it struck

me as a pleasant sort of fooling....

"I suppose you will let me know some day who you are?"

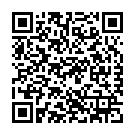

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.