provisions of this "Small

Print!" statement.

[3] Pay a trademark license fee to the Project of 20% of the net profits

you derive calculated using the method you already use to calculate

your applicable taxes. If you don't derive profits, no royalty is due.

Royalties are payable to "Project Gutenberg

Association/Carnegie-Mellon University" within the 60 days following

each date you prepare (or were legally required to prepare) your annual

(or equivalent periodic) tax return.

WHAT IF YOU *WANT* TO SEND MONEY EVEN IF YOU

DON'T HAVE TO?

The Project gratefully accepts contributions in money, time, scanning

machines, OCR software, public domain etexts, royalty free copyright

licenses, and every other sort of contribution you can think of. Money

should be paid to "Project Gutenberg Association / Carnegie-Mellon

University".

*END*THE SMALL PRINT! FOR PUBLIC DOMAIN

ETEXTS*Ver.04.29.93*END*

Over the Sliprails by Henry Lawson

[Note on text: Italicized words or phrases are capitalised. Some obvious

errors have been corrected.]

Over the Sliprails by Henry Lawson

Author of "While the Billy Boils", "When the World was Wide and

Other Verses", "On the Track", "Verses: Popular and Humorous", &c.

Preface

Of the stories in this volume many have already appeared in the

columns of [various periodicals], while several now appear in print for

the first time.

H. L. Sydney, June 9th, 1900.

Contents

The Shanty-Keeper's Wife A Gentleman Sharper and Steelman Sharper

An Incident at Stiffner's The Hero of Redclay The Darling River A

Case for the Oracle A Daughter of Maoriland New Year's Night Black

Joe They Wait on the Wharf in Black Seeing the Last of You Two

Boys at Grinder Brothers' The Selector's Daughter Mitchell on the

"Sex" and Other "Problems" The Master's Mistake The Story of the

Oracle

Over the Sliprails

The Shanty-Keeper's Wife

There were about a dozen of us jammed into the coach, on the box seat

and hanging on to the roof and tailboard as best we could. We were

shearers, bagmen, agents, a squatter, a cockatoo, the usual joker -- and

one or two professional spielers, perhaps. We were tired and stiff and

nearly frozen -- too cold to talk and too irritable to risk the inevitable

argument which an interchange of ideas would have led up to. We had

been looking forward for hours, it seemed, to the pub where we were to

change horses. For the last hour or two all that our united efforts had

been able to get out of the driver was a grunt to the effect that it was

"'bout a couple o' miles." Then he said, or grunted, "'Tain't fur now," a

couple of times, and refused to commit himself any further; he seemed

grumpy about having committed himself that far.

He was one of those men who take everything in dead earnest; who

regard any expression of ideas outside their own sphere of life as trivial,

or, indeed, if addressed directly to them, as offensive; who, in fact, are

darkly suspicious of anything in the shape of a joke or laugh on the part

of an outsider in their own particular dust-hole. He seemed to be always

thinking, and thinking a lot; when his hands were not both engaged, he

would tilt his hat forward and scratch the base of his skull with his little

finger, and let his jaw hang. But his intellectual powers were mostly

concentrated on a doubtful swingle-tree, a misfitting collar, or that

there bay or piebald (on the off or near side) with the sore shoulder.

Casual letters or papers, to be delivered on the road, were matters

which troubled him vaguely, but constantly -- like the abstract ideas of

his passengers.

The joker of our party was a humourist of the dry order, and had been

slyly taking rises out of the driver for the last two or three stages. But

the driver only brooded. He wasn't the one to tell you straight if you

offended him, or if he fancied you offended him, and thus gain your

respect, or prevent a misunderstanding which would result in life-long

enmity. He might meet you in after years when you had forgotten all

about your trespass -- if indeed you had ever been conscious of it -- and

"stoush" you unexpectedly on the ear.

Also you might regard him as your friend, on occasion, and yet he

would stand by and hear a perfect stranger tell you the most outrageous

lies, to your hurt, and know that the stranger was telling lies, and never

put you up to it. It would never enter his head to do so. It wouldn't be

any affair of his -- only an abstract question.

It grew darker and colder. The rain came as if the frozen south were

spitting at your face

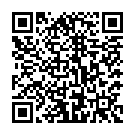

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.