and cursory acquaintance with my kind,

I am inclined to think that the last utterance will formulate, strange as it

may appear, some hope now to us utterly inconceivable. For mankind

is delightful in its pride, its assurance, and its indomitable tenacity. It

will sleep on the battlefield among its own dead, in the manner of an

army having won a barren victory. It will not know when it is beaten.

And perhaps it is right in that quality. The victories are not, perhaps, so

barren as it may appear from a purely strategical, utilitarian point of

view. Mr. Henry James seems to hold that belief. Nobody has rendered

better, perhaps, the tenacity of temper, or known how to drape the robe

of spiritual honour about the drooping form of a victor in a barren strife.

And the honour is always well won; for the struggles Mr. Henry James

chronicles with such subtle and direct insight are, though only personal

contests, desperate in their silence, none the less heroic (in the modern

sense) for the absence of shouted watchwords, clash of arms and sound

of trumpets. Those are adventures in which only choice souls are ever

involved. And Mr. Henry James records them with a fearless and

insistent fidelity to the PERIPETIES of the contest, and the feelings of

the combatants.

The fiercest excitements of a romance DE CAPE ET D'EPEE, the

romance of yard-arm and boarding pike so dear to youth, whose

knowledge of action (as of other things) is imperfect and limited, are

matched, for the quickening of our maturer years, by the tasks set, by

the difficulties presented, to the sense of truth, of necessity--before all,

of conduct--of Mr. Henry James's men and women. His mankind is

delightful. It is delightful in its tenacity; it refuses to own itself beaten;

it will sleep on the battlefield. These warlike images come by

themselves under the pen; since from the duality of man's nature and

the competition of individuals, the life-history of the earth must in the

last instance be a history of a really very relentless warfare. Neither his

fellows, nor his gods, nor his passions will leave a man alone. In virtue

of these allies and enemies, he holds his precarious dominion, he

possesses his fleeting significance; and it is this relation in all its

manifestations, great and little, superficial or profound, and this relation

alone, that is commented upon, interpreted, demonstrated by the art of

the novelist in the only possible way in which the task can be

performed: by the independent creation of circumstance and character,

achieved against all the difficulties of expression, in an imaginative

effort finding its inspiration from the reality of forms and sensations.

That a sacrifice must be made, that something has to be given up, is the

truth engraved in the innermost recesses of the fair temple built for our

edification by the masters of fiction. There is no other secret behind the

curtain. All adventure, all love, every success is resumed in the

supreme energy of an act of renunciation. It is the uttermost limit of our

power; it is the most potent and effective force at our disposal on which

rest the labours of a solitary man in his study, the rock on which have

been built commonwealths whose might casts a dwarfing shadow upon

two oceans. Like a natural force which is obscured as much as

illuminated by the multiplicity of phenomena, the power of

renunciation is obscured by the mass of weaknesses, vacillations,

secondary motives and false steps and compromises which make up the

sum of our activity. But no man or woman worthy of the name can

pretend to anything more, to anything greater. And Mr. Henry James's

men and women are worthy of the name, within the limits his art, so

clear, so sure of itself, has drawn round their activities. He would be the

last to claim for them Titanic proportions. The earth itself has grown

smaller in the course of ages. But in every sphere of human perplexities

and emotions, there are more greatnesses than one--not counting here

the greatness of the artist himself. Wherever he stands, at the beginning

or the end of things, a man has to sacrifice his gods to his passions, or

his passions to his gods. That is the problem, great enough, in all truth,

if approached in the spirit of sincerity and knowledge.

In one of his critical studies, published some fifteen years ago, Mr.

Henry James claims for the novelist the standing of the historian as the

only adequate one, as for himself and before his audience. I think that

the claim cannot be contested, and that the position is unassailable.

Fiction is history, human history, or it is nothing. But it is also more

than that;

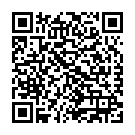

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.