felicity; in which the ruin travels faster than the flying

showers upon the mountain-side, faster 'than a musician scatters

sounds;' in which 'it was' and 'it is not' are words of the self-same

tongue, in the self-same minute; in which the sun that at noon beheld

all sound and prosperous, long before its setting hour looks out upon a

total wreck, and sometimes upon the total abolition of any fugitive

memorial that there ever had been a vessel to be wrecked, or a wreck to

be obliterated.

These cases, though here spoken of rhetorically, are of daily occurrence;

and, though they may seem few by comparison with the infinite

millions of the species, they are many indeed, if they be reckoned

absolutely for themselves; and throughout the limits of a whole nation,

not a day passes over us but many families are robbed of their heads, or

even swallowed up in ruin themselves, or their course turned out of the

sunny beams into a dark wilderness. Shipwrecks and nightly

conflagrations are sometimes, and especially among some nations,

wholesale calamities; battles yet more so; earthquakes, the famine, the

pestilence, though rarer, are visitations yet wider in their desolation.

Sickness and commercial ill-luck, if narrower, are more frequent

scourges. And most of all, or with most darkness in its train, comes the

sickness of the brain--lunacy--which, visiting nearly one thousand in

every million, must, in every populous nation, make many ruins in each

particular day. 'Babylon in ruins,' says a great author, 'is not so sad a

sight as a human soul overthrown by lunacy.' But there is a sadder even

than that,--the sight of a family-ruin wrought by crime is even more

appalling. Forgery, breaches of trust, embezzlement, of private or

public funds--(a crime sadly on the increase since the example of

Fauntleroy, and the suggestion of its great feasibility first made by

him)--these enormities, followed too often, and countersigned for their

final result to the future happiness of families, by the appalling

catastrophe of suicide, must naturally, in every wealthy nation, or

wherever property and the modes of property are much developed,

constitute the vast majority of all that come under the review of public

justice. Any of these is sufficient to make shipwreck of all peace and

comfort for a family; and often, indeed, it happens that the desolation is

accomplished within the course of one revolving sun; often the whole

dire catastrophe, together with its total consequences, is both

accomplished and made known to those whom it chiefly concerns

within one and the same hour. The mighty Juggernaut of social life,

moving onwards with its everlasting thunders, pauses not for a moment

to spare--to pity--to look aside, but rushes forward for ever, impassive

as the marble in the quarry--caring not for whom it destroys, for the

how many, or for the results, direct and indirect, whether many or few.

The increasing grandeur and magnitude of the social system, the more

it multiplies and extends its victims, the more it conceals them; and for

the very same reason: just as in the Roman amphitheatres, when they

grew to the magnitude of mighty cities, (in some instances

accommodating four hundred thousand spectators, in many a fifth part

of that amount,) births and deaths became ordinary events, which, in a

small modern theatre, are rare and memorable; and exactly as these

prodigious accidents multiplied, pari passu, they were disregarded and

easily concealed: for curiosity was no longer excited; the sensation

attached to them was little or none.

From these terrific tragedies, which, like monsoons or tornadoes,

accomplish the work of years in an hour, not merely an impressive

lesson is derived, sometimes, perhaps, a warning, but also (and this is

of universal application) some consolation. Whatever may have been

the misfortunes or the sorrows of a man's life, he is still privileged to

regard himself and his friends as amongst the fortunate by comparison,

in so far as he has escaped these wholesale storms, either as an actor in

producing them, or a contributor to their violence--or even more

innocently, (though oftentimes not less miserably)--as a participator in

the instant ruin, or in the long arrears of suffering which they entail.

The following story falls within the class of hasty tragedies, and sudden

desolations here described. The reader is assured that every incident is

strictly true: nothing, in that respect, has been altered; nor, indeed,

anywhere except in the conversations, of which, though the results and

general outline are known, the separate details have necessarily been

lost under the agitating circumstances which produced them. It has

been judged right and delicate to conceal the name of the great city, and

therefore of the nation in which these events occurred, chiefly out of

consideration for the descendants of one person concerned in the

narrative:

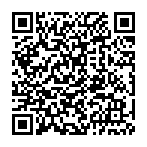

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.