I was completely puzzled.

Everything appeared to me foreign, strange, and unnatural, and Prince

Le Boo, or any other savage, never stared or wondered more than I did.

Of most things I knew not the use, of many not even the names. I was

literally a savage, but still a kind and docile one. The day after my new

clothes had been put on, I was summoned into the parlour. Mr

Drummond and his wife surveyed me in my altered habiliments, and

amused themselves at my awkwardness, at the same time that they

admired my well-knit, compact, and straight figure, set off by a fit, in

my opinion much too straight. Their little daughter Sarah, who often

spoke to me, went up and whispered to her mother. "You must ask

papa," was the reply. Another whisper, and a kiss, and Mr Drummond

told me I should dine with them. In a few minutes I followed them into

the dining-room and for the first time I was seated to a repast which

could boast of some of the supernumerary comforts of civilised life.

There I sat, perched on a chair with my feet swinging close to the

carpet, glowing with heat from the compression of my clothes and the

novelty of my situation, and all that was around me. Mr Drummond

helped me to some scalding soup, a silver spoon was put into my hand,

which I twisted round and round, looking at my face reflected in

miniature on its polish.

"Now, Jacob, you must eat the soup with the spoon," said little Sarah,

laughing; "we shall all be done. Be quick."

"Take it coolly," replied I, digging my spoon into the burning

preparation, and tossing it into my mouth. It burst forth from my

tortured throat in a diverging shower, accompanied with a howl of pain.

"The poor boy has scalded his mouth," cried the lady, pouring out a

tumbler of water.

"It's no use crying," replied I, blubbering with all my might; "what's

done can't be helped."

"Better that you had not been helped," observed Mr Drummond, wiping

off his share of my liberal spargification from his coat and waistcoat.

"The poor boy has been shamefully neglected," observed the

good-natured Mrs Drummond. "Come, Jacob, sit down and try it again;

it will not burn you now."

"Better luck next time," said I, shoving in a portion of it, with a great

deal of tremulous hesitation, and spilling one-half of it in its transit. It

was now cool, but I did not get on very fast; I held my spoon awry, and

soiled my clothes.

Mrs Drummond interfered, and kindly showed me how to proceed;

when Mr Drummond said, "Let the boy eat it after his own fashion, my

dear--only be quick, Jacob, for we are waiting."

"Then I see no good losing so much of it, taking it in tale," observed I,

"when I can ship it all in bulk in a minute." I laid down my spoon, and

stooping my head, applied my mouth to the edge of the plate, and

sucked the remainder down my throat without spilling a drop. I looked

up for approbation, and was very much astonished to hear Mrs

Drummond quietly observe, "That is not the way to eat soup."

I made so many blunders during the meal that little Sarah was in a

continued roar of laughter; and I felt so miserable, that I heartily wished

myself again in my dog-kennel on board of the lighter, gnawing biscuit

in all the happiness of content and dignity of simplicity. For the first

time I felt the pangs of humiliation. Ignorance is not always debasing.

On board of the lighter, I was sufficient for myself, my company, and

my duties. I felt an elasticity of mind, a respect for myself, and a

consciousness of power, as the immense mass was guided through the

waters by my single arm. There, without being able to analyse my

feelings, I was a spirit guiding a little world; and now, at this table, and

in company with rational and well-informed beings, I felt humiliated

and degraded; my heart was overflowing with shame, and at one

unusual loud laugh of the little Sarah, the heaped up measure of my

anguish overflowed, and I burst into a passion of tears. As I lay with

my head upon the table-cloth, regardless of those decencies I had so

much feared, and awake only to a deep sense of wounded pride, each

sob coming from the very core of my heart, I felt a soft breathing warm

upon my cheek, that caused me to look up timidly, and I beheld the

glowing and beautiful face of little Sarah, her eyes filled with tears,

looking so softly and beseechingly at me, that I felt at once

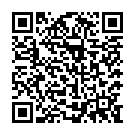

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.