Among My Books, Second Series

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Among My Books, by James Russell

Lowell Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to

check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or

redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook.

This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project

Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the

header without written permission.

Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the

eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is

important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how

the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a

donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved.

**Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts**

**eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since

1971**

*****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of

Volunteers!*****

Title: Among My Books

Author: James Russell Lowell

Release Date: July, 2005 [EBook #8509] [This file was first posted on

July 18, 2003]

Edition: 10

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK, AMONG

MY BOOKS ***

E-text prepared by Ted Garvin, Thomas Berger, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team

AMONG MY BOOKS

Second Series

by JAMES RUSSELL LOWELL

To R.W. EMERSON.

A love and honor which more than thirty years have deepened, though

priceless to him they enrich, are of little import to one capable of

inspiring them. Yet I cannot deny myself the pleasure of so far

intruding on your reserve as at least to make public acknowledgment of

the debt I can never repay.

CONTENTS.

DANTE

SPENSER

WORDSWORTH

MILTON

KEATS

DANTE.[1]

On the banks of a little river so shrunken by the suns of summer that it

seems fast passing into a tradition, but swollen by the autumnal rains

with an Italian suddenness of passion till the massy bridge shudders

under the impatient heap of waters behind it, stands a city which, in its

period of bloom not so large as Boston, may well rank next to Athens

in the history which teaches _come l' uom s' eterna_.

Originally only a convenient spot in the valley where the fairs of the

neighboring Etruscan city of Fiesole were held, it gradually grew from

a huddle of booths to a town, and then to a city, which absorbed its

ancestral neighbor and became a cradle for the arts, the letters, the

science, and the commerce[2] of modern Europe. For her Cimabue

wrought, who infused Byzantine formalism with a suggestion of nature

and feeling; for her the Pisani, who divined at least, if they could not

conjure with it, the secret of Greek supremacy in sculpture; for her the

marvellous boy Ghiberti proved that unity of composition and grace of

figure and drapery were never beyond the reach of genius;[3] for her

Brunelleschi curved the dome which Michel Angelo hung in air on St.

Peter's; for her Giotto reared the bell-tower graceful as an Horatian ode

in marble; and the great triumvirate of Italian poetry, good sense, and

culture called her mother. There is no modern city about which cluster

so many elevating associations, none in which the past is so

contemporary with us in unchanged buildings and undisturbed

monuments. The house of Dante is still shown; children still receive

baptism at the font (_il mio bel San Giovanni_) where he was

christened before the acorn dropped that was to grow into a keel for

Columbus; and an inscribed stone marks the spot where he used to sit

and watch the slow blocks swing up to complete the master-thought of

Arnolfo. In the convent of St. Mark hard by lived and labored Beato

Angelico, the saint of Christian art, and Fra Bartolommeo, who taught

Raphael dignity. From the same walls Savonarola went forth to his

triumphs, short-lived almost as the crackle of his martyrdom. The plain

little chamber of Michel Angelo seems still to expect his return; his last

sketches lie upon the table, his staff leans in the corner, and his slippers

wait before the empty chair. On one of the vine-clad hills, just without

the city walls, one's feet may press the same stairs that Milton climbed

to visit Galileo. To an American there is something supremely

impressive in this cumulative influence of the past full of inspiration

and rebuke, something saddening in this repeated proof that moral

supremacy is the only one that leaves monuments and not ruins behind

it. Time, who with us obliterates the labor and often the names of

yesterday, seems here to have spared almost the prints of the care

piante that shunned the sordid paths of worldly honor.

Around the courtyard of the

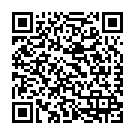

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.